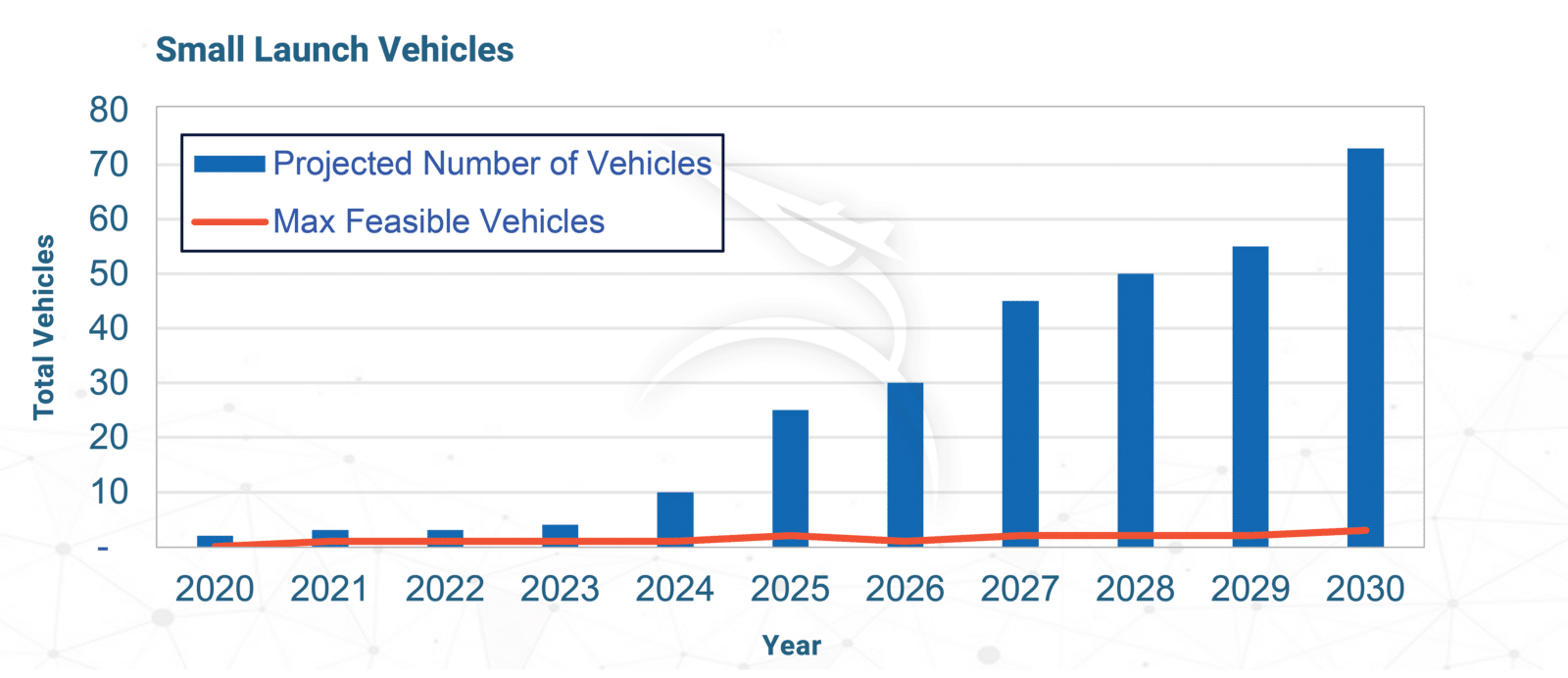

As we wrote in our full-length Insight article back in August 2022, SpaceWorks has long anticipated a reduction in the number of launch vehicle companies in the market – especially at the low end of the payload range. For small satellite launchers, our quantitative analysis predicted the long-term market will support perhaps only five healthy small satellite launchers worldwide and even fewer (two) in the near term.

Last week’s announcement that Virgin Orbit (VORB) has declared bankruptcy is a disappointment to industry watchers, but the news should not come as a a total surprise. Others have written at length about the company’s financial struggles and leadership challenges, but our unique perspective at SpaceWorks comes from expertise at the intersection of aerospace engineering and economics. We understand that developing a new orbital launch vehicle is hard, and we know that air-launch is amongst the hardest options to pursue. We abandoned our own attempt to develop the air-launched GOLauncher 2 vehicle under our Generation Orbit subsidiary in 2015. Northrop Grumman’s Pegasus, Swiss Space Systems (S3), the Stratolaunch/SpaceX Falcon partnership, Air Launch LLC, DARPA’s ALASA, and now Virgin Orbit’s LauncherOne highlight a common theme of unmet potential due to technical and/or business model failures. Although air-launch looks good on paper – offering launch site flexibility, standoff launch, weather avoidance, responsiveness, etc. – it has thus far proven inviable at the low launch rates achieved. Air-launch necessitates developing three flight configurations – a rocket, an aircraft, and the “combined system” – which has a multiplicative impact on complexity. Each part of that system brings its own set of regulatory, safety, financial, and technical problems. Relative to traditional vertical takeoff rockets, the upfront costs are greater and development times are longer – precisely the opposite of what’s needed in today’s competitive and dynamic commercial market.

The team at Virgin Orbit pulled off a notable accomplishment in building and flying LauncherOne. However, as a product, LauncherOne was unable to navigate the economic realities, and it failed to demonstrate an ability to generate the revenue needed to sustain its operations. Some simple financial calculations illustrate this daunting challenge. At Virgin Orbit’s average expenditure rate of $50M/quarter, the company would need to launch at least every few weeks to cover its operating costs. Further, assuming an optimistic profit margin of only $1.5M per launch, the venture was unlikely to ever recoup the to-date development costs estimated to be over $1B (650+ launches at that margin).

Virgin Orbit’s exit was the first of the recently SPAC’d companies, but we do not expect it to be the last, especially with five other NSI (NewSpace Index) companies currently trading well below $1 per share and at risk of being delisted. Failure is a painful but natural part of growth. As today’s marketplace transforms into the thriving space economy we all wish for, weaker concepts and business models will fail, stronger approaches will succeed, and new entrants will jump into the fray.

Photo: Virgin Orbit